The Rolling Stones – Beggars Banquet

Beggars Banquet, the seventh studio album by The Stones, marked a return to the band’s R&B roots. Following the long sessions for the previous album Their Satanic Majesties Request in 1967 and the departure of producer and manager Andrew Loog Oldham, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards hired producer Jimmy Miller, the partnership proved to be a success and Miller would work with the band until 1973.

Texan-born Miller had been working in the UK, producing artists like Traffic and The Spencer Davis Group, with whom he had co-written the song I’m A Man. Stones engineer Glyn Johns was aware of his work, and recommended Miller to Mick Jagger when Jagger expressed the desire to hire an American producer. The famously acerbic Johns apparently said, ‘I [thought] ‘I don’t think my ego could stand having some bloody yank in here telling me what sound to get for The Rolling Stones’. Miller worked well with Johns and the Stones, helping to create some of their most memorable tracks, and beefing up their rhythm tracks, sometimes even playing drums himself, as he did on You Can’t Always Get What You Want and Happy, amongst others.

One of the first tracks cut during the sessions, which occurred at Olympic Studios in Barnes, south London between March and May 1968, was Jumpin’ Jack Flash, which was released only as a single in May. Like The Beatles and other acts in the 1960s, it was common practice to release a new song as a single in advance of a new album, on which the single wouldn’t be included. It was felt that core fans would buy the album anyway, and they wouldn’t want to feel they’d been sold the same thing twice, whereas more casual fans would stick with just singles.

Jumpin’ Jack Flash became a major hit (reaching #1 in the UK and #3 in the US) and became one of the group’s most popular and recognisable songs. Richards has stated that he and Jagger wrote the lyrics while staying at Richards’ country house, where they were awakened one morning by the sound of gardener Jack Dyer walking past the window. When Jagger asked what the noise was, Richards responded, ‘Oh, that’s Jack – that’s jumpin’ Jack.

Beggars Banquet was to be Brian Jones‘ last full album with the Rolling Stones; he had become so dysfunctional by the summer of 1969 that the band had to ask him to leave. In the meantime, his contributions to Beggars Banquet showed his astounding versatility: in addition to slide guitar on No Expectations, he played harmonica on Dear Doctor, Prodigal Son and Parachute Woman (along with Mick Jagger). He also contributed sitar and tambura to Street Fighting Man, played mellotron on Jigsaw Puzzle and Stray Cat Blues, and sang backing vocals on Sympathy For The Devil.

Sympathy For The Devil itself started the album in stark contrast to the psychedelic meanderings of the previous album. Largely a Jagger composition, the working title of the song was ‘The Devil Is My Name’, and it is sung as a first-person narrative from the point of view of Lucifer. In a 1995 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Jagger said, ‘I think that was taken from an old idea of Baudelaire’s, I think, but I could be wrong…..But it was an idea I got from French writing. And I just took a couple of lines and expanded on it. I wrote it as sort of like a Bob Dylan song.’ Keith Richards suggested changing the tempo from its original mid-pace and using additional percussion, to turn it into a samba, complete with exhorting backing vocals, as documented in Jean-Luc Godard’s impenetrable One Plus One film, where he captured the recording session at London’s Olympic Studios.

Charlie Watts said, of the tempo, in the 2003 book According To The Rolling Stones: ‘We had a go at loads of different ways of playing it; in the end I just played a jazz Latin feel in the style of Kenny Clarke, [like he] would have played on A Night In Tunisia – not the actual rhythm he played, but the same styling.’

The album is notable for its use of acoustic instruments on songs like Dear Doctor, No Expectations and Factory Girl, some of which use musicians from outside the group, such as Stones’ regular Nicky Hopkins on piano, Rocky Dijon on conga drums, and Family’s Ric Grech, who played fiddle on Factory Girl.

Of Factory Girl, Charlie Watts said in 2003, ‘I was doing something you shouldn’t do, which is playing the tabla with sticks instead of trying to get that sound using your hand, which Indian tabla players do, though it’s an extremely difficult technique and painful if you’re not trained.’ Keith Richards commented in the same year: ‘To me Factory Girl felt something like Molly Malone, an Irish jig; one of those ancient Celtic things that emerge from time to time, or an Appalachian song. In those days I would just come up and play something, sitting around the room. I still do that today. If Mick gets interested I’ll carry on working on it; if he doesn’t look interested, I’ll drop it, leave it and say, ‘I’ll work on it and maybe introduce it later.’

Originally titled and recorded as Did Everyone Pay Their Dues?, (with the same music but different lyrics), Street Fighting Man is known as one of Jagger & Richards’ most political songs. Jagger allegedly wrote it about then-student activist Tariq Ali after Jagger attended a March 1968 anti-war rally at London’s US embassy, during which mounted police attempted to control a crowd of 25,000. He was also inspired by the violence among that year’s student rioters on the Left Bank of Paris, saying in a 1995 interview with Jann Wenner in Rolling Stone magazine: ‘Yeah, it was a direct inspiration, because by contrast, London was very quiet…It was a very strange time in France. There was all this violence going on. I mean, they almost toppled the government in France; DeGaulle went into this complete funk, as he had in the past, and he went and sort of locked himself in his house in the country. And so the government was almost inactive.’

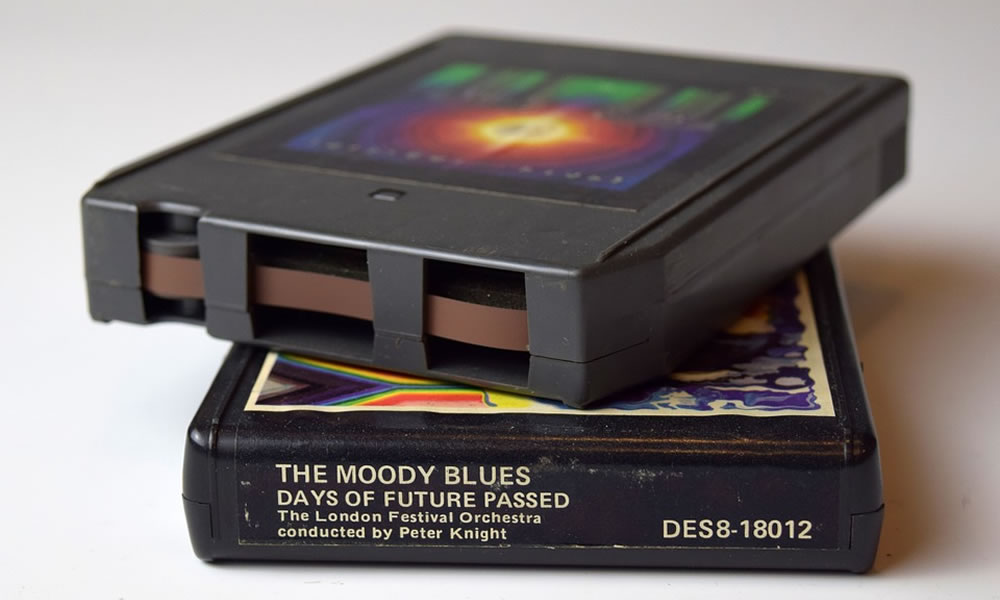

The basic backing track was very lo-fi, being recorded on an early mono Philips cassette recorder, which induced distortion and compression into the track, including the distinctive acoustic guitar introduction. Charlie Watts said in 2003: Street Fighting Man was recorded on Keith’s cassette with a 1930s toy drum kit called a London Jazz Kit Set, which I bought in an antiques shop, and which I’ve still got at home. It came in a little suitcase, and there were wire brackets you put the drums in; they were like small tambourines with no jangles… The snare drum was fantastic because it had a really thin skin with a snare right underneath, but only two strands of gut… Keith loved playing with the early cassette machines because they would overload, and when they overload they sounded fantastic, although you weren’t meant to do that. We usually played in one of the bedrooms on tour. Keith would be sitting on a cushion playing a guitar and the tiny kit was a way of getting close to him. The drums were really loud compared to the acoustic guitar and the pitch of them would go right through the sound. You’d always have a great backbeat.’

Bruce Springsteen included Street Fighting Man in the encores of some of his 1985 Born in the U.S.A. Tour shows, and said: ‘That one line, ‘What can a poor boy do but sing in a rock and roll band?’ is one of the greatest rock and roll lines of all time. …’

Street Fighting Man was released as Beggars Banquet’s lead single on August 31, 1968, in the US, but was kept out of the Top 40 (reaching #48) of the US charts in response to many radio stations’ refusal to play the song based on what were perceived as subversive lyrics.

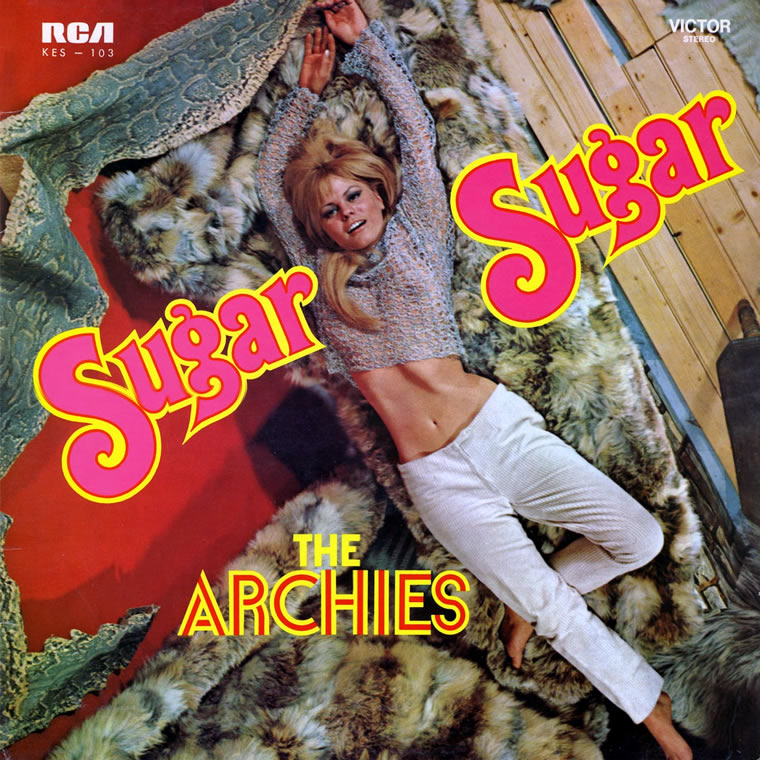

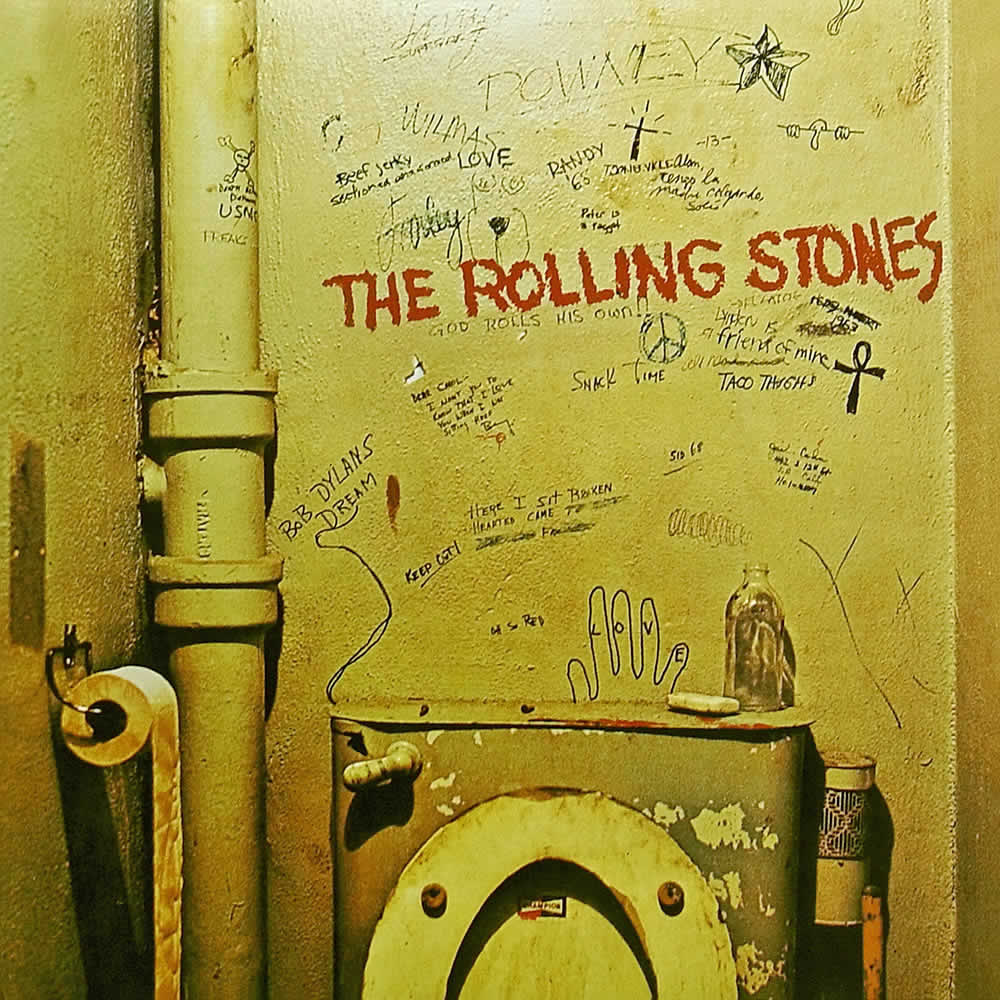

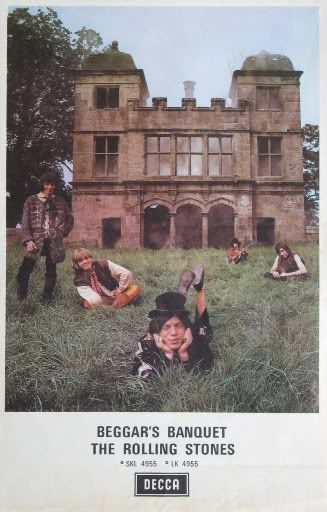

When Beggars Banquet was completed, both the UK’s Decca Records and London Records in the US rejected the planned cover design – a graffiti-covered lavatory wall. The band initially refused to change the cover, resulting in several months’ delay, but by November, the Stones gave in, allowing the album to be released in December with a simple white cover imitating an invitation card, complete with an RSVP.

The band held a rambunctious release party for the album’s release at the elegant and historic Gore Hotel in Queen’s Gate, close to the Royal Albert Hall in London. Initially, the band had wanted to launch the album with a party at the Tower of London but with that historic venue unavailable, they opted for the Elizabethan room of the Gore. The band, dressed as beggars, and their VIP media guests, sat down in candlelight to be served a seven-course dinner by a coterie of corset-busting serving wenches.

The album fared as well as Stones albums of the time, hitting #3 in the UK, and #5 in the US, but it has held up much better than the psychedelia of the previous releases and marked the start of a run of albums that are still regarded as Stones classics: Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile On Main Street. The triumph of the Hyde Park concert and the misery of the Altamont tragedy were still in front of them, so the Stones in ’68 could still enjoy their position at the forefront of the British music scene before the darkness of the 1970s engulfed us all.

In August 2002, ABKCO Records reissued Beggars Banquet as a newly remastered LP and SACD/CD hybrid disc, remastered to run at the correct speed. In its original version, Beggars Banquet played at a slower speed than it was recorded, which altered not only the tempo but the key of each song. It was released once again in 2010 by Universal Music Enterprises in a Japanese only SHM-SACD version.