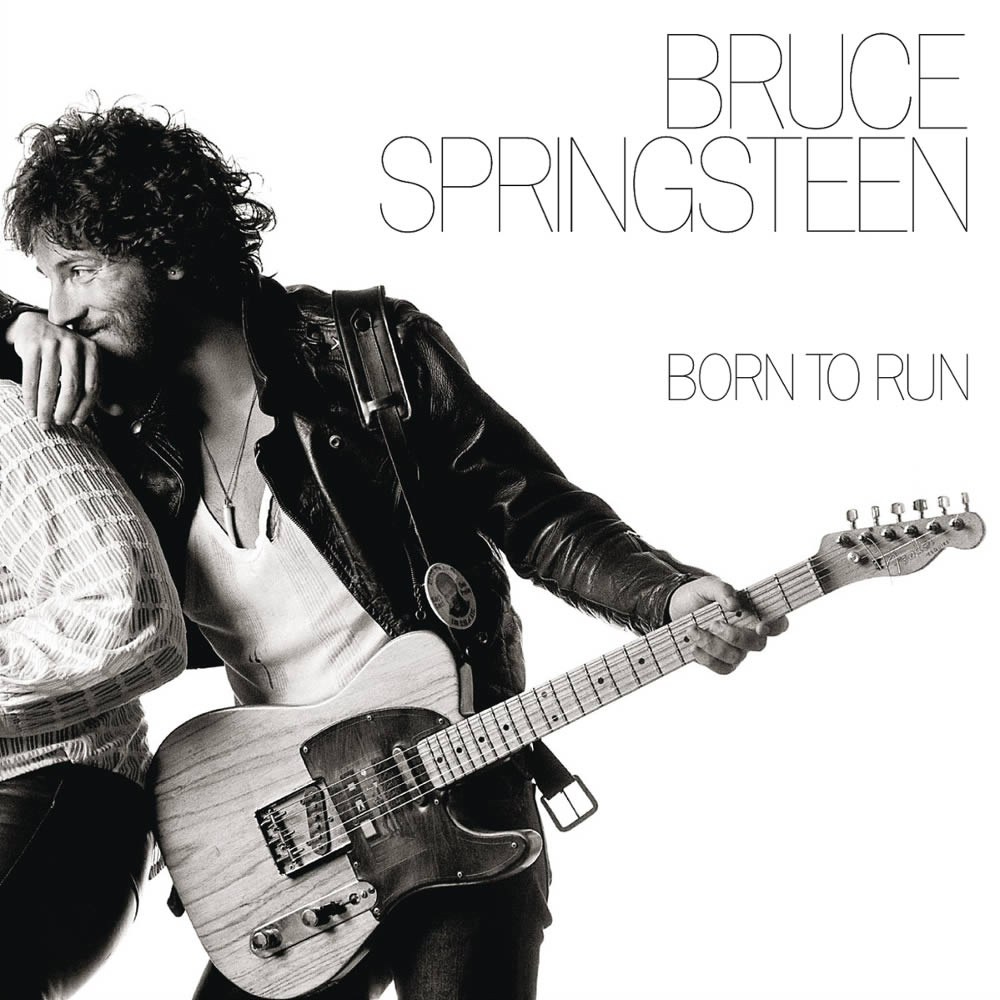

Bruce Springsteen – Born To Run

Looking back on the making of Born To Run, its maker Bruce Springsteen had this to say about it: ‘Born To Run had the feeling of that one, endless summer night. The whole record feels like it could all be taking place in the course of one evening, in all these different locations. Everything is filled with that tension of somebody struggling, trying to find some other place.’

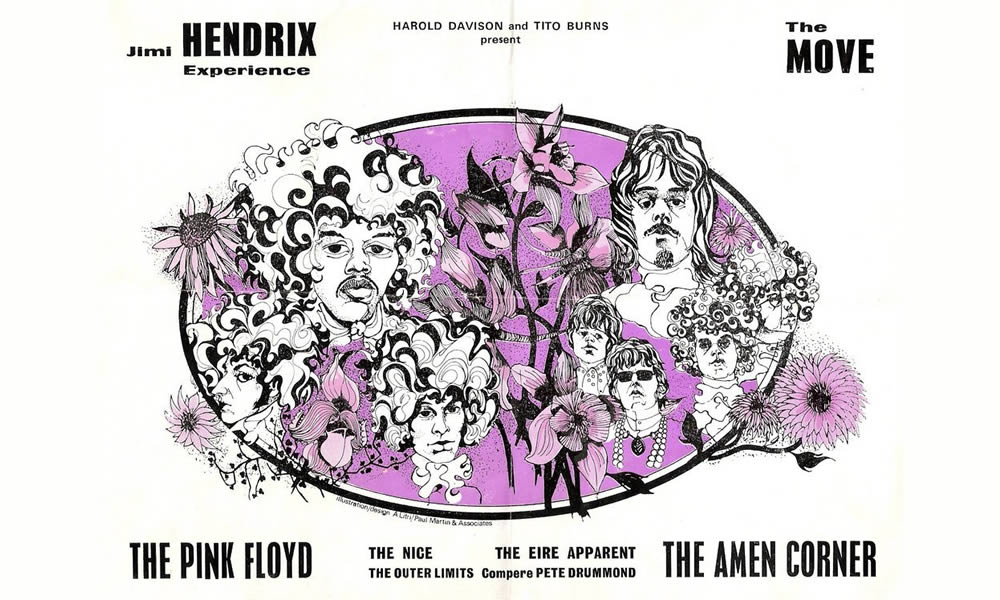

The skinny, tousled 24-year-old Jersey Shore songwriter had been hailed as the new Bob Dylan by his A&R man at Columbia Records, John Hammond, who knew what he was talking about, since he had discovered the original. But Born To Run, the songwriter’s third, was his make or break album; his first two albums hadn’t sold enough to convince Columbia that he wasn’t a flop, so this could’ve been his last chance. The thing is, the first two albums (Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ, and The Wild, The Innocent and The E Street Shuffle), were good records, and Springsteen’s songwriting was already so well regarded that The Hollies had covered one of his songs – and David Bowie had covered two, having seen him perform at Max’s Kansas City in 1972. But within the media the ‘new Dylan’ tag was in danger of tainting Springsteen’s’ chances of success, so it was out on the road that Springsteen was making his mark.

Luckily he had the crack E Street Band to back him up, plus a love of soul, Motown, R&B and pop that allowed him to switch from one genre to another in an instant, giving 100% nightly in a welter of excitement. Springsteen’s live shows were rapidly becoming an open secret that hipsters couldn’t afford to miss, and one who didn’t was the highly respected Jon Landau, a contributor to Rolling Stone magazine based in Boston, Massachusetts. His rave review of a Springsteen show, in which the quote ‘I have seen rock n’ roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen’ was quoted both incorrectly and out of context, could have been another unwelcome millstone, but in fact, in the short term, it persuaded Columbia execs that perhaps, just perhaps, Springsteen was worth sticking with.

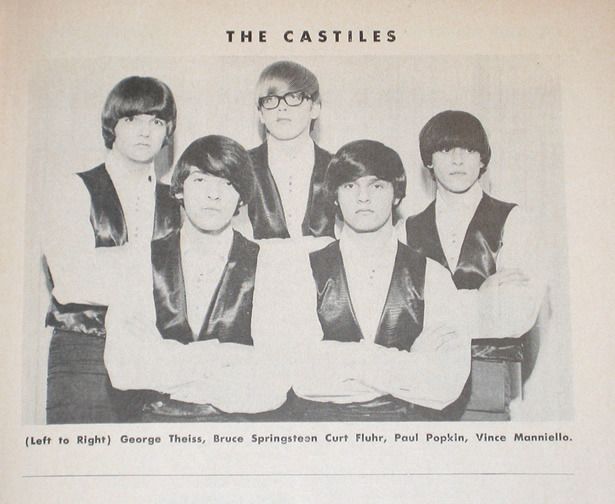

The other major factor for Springsteen’s career in 1975 was one ground-breaking song, ironically one of the most complicated he would ever record: Born To Run. The title came to Springsteen as something that sounded good and made a statement, but the pursuit of its recorded perfection was to take him nearly a year. He had signed to Columbia in May 1972, recruited the E Street Band from former New Jersey band mates, and hit the road, releasing his debut album in January 1973. The second album followed in November, including the future show-closer Rosalita, but also the long, jazzy New York City Serenade, featuring the keyboards of the prodigiously talented David Sancious. So in May 1974, when Springsteen, opening for Bonnie Raitt at a show in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was able to evoke the multifarious images of street poet, folk drifter, jazz boulevardier and out and out rocker, it was understandable that, because it was hard to categorise him, it would be to his benefit to create one defining anthem.

Here’s part of what Jon Landau said in the Boston Real Paper after a preamble about feeling old and jaded (Landau was 27 at the time): ‘… tonight there is someone I can write of the way I used to write, without reservations of any kind. Last Thursday, at the Harvard Square theatre, I saw my rock’n’roll past flash before my eyes. And I saw something else: I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen. And on a night when I needed to feel young, he made me feel like I was hearing music for the very first time. When his two-hour set ended I could only think, can anyone really be this good; can anyone say this much to me, can rock’n’roll still speak with this kind of power and glory? And then I felt the sores on my thighs where I had been pounding my hands in time for the entire concert and knew that the answer was yes.’

Rolling Stone and other papers were soon trumpeting Landau’s endorsement. So all he had to do was live up to it. Born To Run was an important step forward in Springsteen’s musical journey because it became a door into Part Two of his career, where he mixed up all his disparate elements into one new version – contemplative, wistful, triumphant, hopeful, and rocking. Springsteen debuted the song live in May / June 1974, then decamped back to the same studio used on the first two albums: 914 Sound Studios, a small studio in Blauvelt, New York, out at the very fringe of the northern suburbs west of the Hudson. Mike Appel, a music producer and publisher, had signed Springsteen to a production deal, and then, at Springsteen’s request, become his manager, securing the release of the recordings on CBS. Springsteen and Appel co-produced their albums, but at 914 the 1974 sessions were a struggle to realise Springsteen’s vision.

In the book Songs, Springsteen commented: ‘One day I was… working on some song ideas, and the words ‘born to run’ came into my head. At first I thought it was the name of a movie or something I’d seen on a car spinning round the Circuit, but I couldn’t be certain.’ Working out the arrangement on live dates with the E Street Band, the song was in the tradition of the long pieces on the first two albums, but Springsteen was determined, as he put it, to ‘deliver its message in less time and with a shorter burst of energy’.

Springsteen: ‘Born To Run… proved to be the key to my songwriting for the rest of the record. Lyrically, I was entrenched in classic rock and roll images, and I wanted to find a way to use those images without their feeling anachronistic.’ The backing track featured The E Street band’s regular keyboard player David Sancious, and Ernest ‘Boom’ Carter, a replacement drummer for the departed Vini ‘Mad Dog’ Lopez, who had played on the first two albums, leaving in February 1974 after a dustup with the band’s management. Carter was a more jazz-oriented player who nevertheless did a fine job on Born To Run. However, having been part of a session on the track on August 6th, according to Backstreets magazine, within 2 weeks Carter quit the band for a career in jazz, along with David Sancious.

Money was very tight, and CBS Records were looking for some action, but The E Street Band took a further step into its second phase when, in relatively short order, new keyboardist Roy Bittan and drummer Max Weinberg were recruited, which at least gave the band a full complement of players with which to carrying on making tracks, and, as importantly, playing gigs, because all the band members had financial commitments.

Springsteen sent a work in progress version of Born To Run to Jon Landau and, in October 1974, when he returned to Boston to play at the Music Hall, he and Landau sat down for a long discussion of how to make a quantum leap from the first albums to world-class recordings. When Landau subsequently relocated to New York, he was to join Springsteen’s team as co-producer with Appel, having previously convinced Springsteen to leave Blauvelt and move to a premier league recording studio, the Record Plant in Manhattan. Landau later stated, ‘We knew exactly what we wanted, we were not in it to do something average. We were not in it to get any particular song on the radio. We were in it to do something great.’

The massive Phil Spector sound on almost every song touched on the central mythical image of the rock ‘n’ roll era – Springsteen has said that he wanted Born To Run to sound like ‘Roy Orbison singing Bob Dylan, produced by Spector’. It took Bruce and his band months in total to record the title track, with versions including string section overdubs, a choir on the chorus and one with a double-tracked lead vocal. Bruce’s friend, guitarist Steve Van Zandt, a veteran of early Springsteen bands and who joined the E Street Band during the album sessions, now laughs at the thought of it. ‘Anytime you spend six months on a song, there’s something not exactly going right. A song should take about three hours.’

As Springsteen stated in one interview, ‘I’m still fiddling with the words for the new single, but I think it will be good’. He wasn’t wrong: on 3rd November 1974, Springsteen appeared with DJ Ed Sciaky on WMMR in Philadelphia, with a surprise for listeners that day: the radio premiere of Born To Run. With an astonishing 9 months to go before the album saw the light of day, and with no confirmed album release date, various radio stations in the US began to play Born To Run. Their early endorsement had two effects: when the official single was finally universally available, radio programmers jumped on it and it became an instant smash; and CBS Records became convinced that their signing had the capability to create hits, becoming much more supportive of Springsteen and the band.

Of course, it also created a ton of pressure to get the record finished and march the quality and power of the title cut. Springsteen knew that the stakes for the third album were high, and recording the rest of the album proved just as challenging for all concerned. New keyboardist Roy Bittan recalled ‘We were recording epics at the time,’ he recalled, ‘I mean Jungleland and Backstreets are not easy songs to record.’ Bittan maintained, ‘It’s like trying to drive a Grand Prix course: Every time you go around one turn, there’s another.’

Springsteen was struggling to get on tape the sound he had in his head, with 18-hour recording sessions becoming a regular occurrence. During these sessions, to stay awake, engineer Jimmy Iovine would take a piece of gum, throw it away, and chew on the aluminum wrapping, counting on the pain to keep him awake.

All in all, the album took more than 14 months to record and at the end, Springsteen was miserable: ‘After it was finished? I hated it! I couldn’t stand to listen to it. I thought it was the worst piece of garbage I’d ever heard.’ Jon Landau, as co-producer, helped persuade him to let go. According to writer Dave Marsh, Landau called Springsteen and said, ‘Look, you’re not supposed to like it. You think Chuck Berry sits around listening to ‘Maybelline’ and when he does hear it, don’t you think he wishes a few things could be changed.? C’mon, it’s time to put the record out.’

Springsteen looked at different titles for the release, considering American Summer, The Legend of Zero & Blind Terry, From the Churches to the Jails, War and Roses, and The Hungry and the Hunted but in the end, the album was named after the single, which burnt up the airwaves when finally officially released, alongside the album, in August 1975. In terms of the original LP’s sequencing, Springsteen had originally planned to begin and end the album with alternative versions of Thunder Road, but eventually adopted a ‘four corners’ approach, as the songs beginning each side (Thunder Road and Born to Run) were uplifting odes to escape, while the songs ending each side (Backstreets and Jungleland) were sad epics of loss, betrayal, and defeat.

Born To Run launched Springsteen towards mega-stardom in 1975, famously getting him on the covers of Time and Newsweek simultaneously, and seeing the album’s release accompanied by a $250,000 promotional campaign by Columbia making use of Landau’s ‘I saw rock ‘n’ roll future’ quote. In 2005, on the 30th anniversary of the album’s release, Springsteen eventually came around to appreciate what he had accomplished, admitting ‘It’s embarrassing to want so much, and to expect so much from music, except sometimes it happens: The Sun Sessions, Highway 61, Sgt. Pepper’s, The Band, Robert Johnson, Exile On Main Street, Born To Run.. – whoops, I meant to leave that one out.’

Mitch Darnell

July 22, 2021 at 3:18 pm

The Boss deeply touches such a wide variety of souls – Starting with those New Jersey denizen who live(d) the same sentimentality Bruce grew up with… To many of us around the globe who’ve never stepped foot into his “Hometown”, or anywhere in the vicinity!

Great article here on the few geniuses who saw that Bruce Springsteen had and has something that perhaps no other musician or artist has ever had. Bruce is a genius inspired by heart and the desire to give to others.